Brown road signs usually point towards something interesting.

This one says, ‘Saxon church’.

We’re on holiday, not in a hurry. Tired – but intrigued enough to make the turn.

It’s been a day of surprises, beginning with this morning …

Mist lingers in the warm air of the Indian Summer. Cresting a hill we find ourselves driving through glorious, dramatic, English countryside – and this on a road from one major industrial city to another.

Not what we expected, in our ignorance.

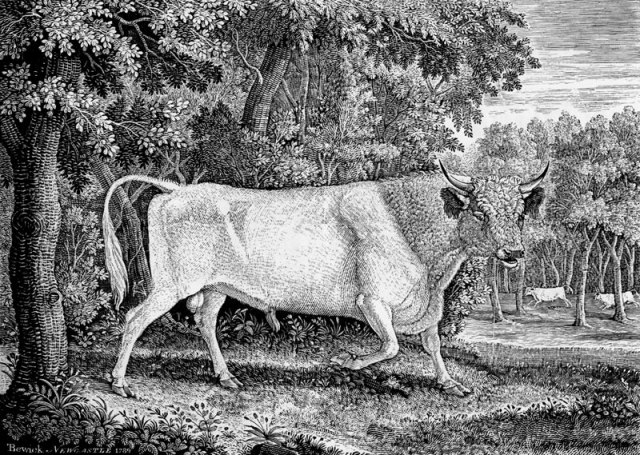

We’re looking for the house where Thomas Bewick – eighteenth century artist and master engraver – lived.

A bridge we need to cross is closed and we’re soon lost in a mess of semi-industrial, semi-rural roads. I blame the map. It’s such a tiny scale that I can’t tell where we are half the time. But eventually we pull into a small car park – and into our second surprise of the day.

Because, as we step into the garden, time slips.

Gone are the noisy roads, the industrial estates and lorries. We’re in Bewick’s world. His trees, his fields, his ox. (Actually, two donkeys, now).

Bewick’s birds are famous, but his rural scenes are gems. Usually, something obvious is happening in the foreground – but look carefully and there’s often something odd going on in the background.

And so it is when, on our way back, we take that brown-signed detour.

As we follow the minor road it feels less and less like the kind of place we’re likely to find an ancient church.

Pretty countryside, mostly, but the villages are real, if you know what I mean. Not second-home charming.

We’re in County Durham, north-eastern England.

Rural beauty. Towns and cities brimming with historic interest. But also a place of industry. Where mining was maybe not king, but certainly a VIP.

And these villages speak of decline.

Mining, shipbuilding, steel. Dead – or dying.

Farming, still, of course, but increasingly mechanised.

So where do people work, now? Or do they? How many call-centres are there in the rural north east?

At last we reach the village.

We’re both feeling dubious. It’s tried its best, is almost pretty as we descend the house-lined hill. But it becomes visibly less affluent the further we go.

And there it is.

Darkened stone. Taller than expected. Set within a graveyard, a wall and a locked iron gate. The church is on a kind of island – the road circles round it before returning up the hill.

The church is on a kind of island – the road circles round it before returning up the hill.

A large, attractive pub, the Saxon Arms, stands on one corner, a little higher up in the world.

Round the back of the church, a strip of small, 1960s terraced houses lines the far side of the road.

A notice on the church gate tells us the key’s at number 28.

Within a few minutes the padlock’s off the gate. On the second attempt we manage to unlock the church door and we’re inside, with timed lights for illumination that project eerie stars on the walls.

Within a few minutes the padlock’s off the gate. On the second attempt we manage to unlock the church door and we’re inside, with timed lights for illumination that project eerie stars on the walls.

It’s like no other Saxon church I’ve seen.

It’s not just the height – or the remains of wall painting, or the whitewash. It’s not the Roman stones or the engraving of the cross. I don’t know – it just feels different.

Possibly the oldest Saxon church in England, at around AD 675, it was nearly lost. The village had a new, Victorian church, up the hill. But one man rallied to the defence of the decaying Saxon edifice, managed to restore it, enlist locals in its maintenance – and the ‘modern’ upstart was demolished.

The village itself was ‘remodelled’ in the 1960s.

I’ll leave the pictures from the church to speak for themselves – I’m just flummoxed by that remodelled village. Of which I take no pictures.

A woman and her dog, the key-holders, live at number 28. The dog, she says, likes to sit and watch the world go by.

Judging by the church guest book, she’s watched quite a few adventurous souls trek by. Most recently, from Scandinavia, Germany, Canada. And I wonder – what did they think of this place?

Accumulated experiences can, I know, coalesce and emerge as prejudices. And I do tend to assume things, despite finding out, time and again, that I’m wrong.

But I suspect some of the first people to live in that terrace of houses bought their homes off local councils in the boom times. And perhaps, more recently, lived to regret it.

One house, a couple of doors down from where the dog sits world-watching, boasts a ‘sold’ sign. On my return I check it out on a property website.

Before I tell you what I discovered, there’s something important you need to know.

Average house prices in July 2014* were:

- England £284,000

- London £514,000.

The three-bedroomed house by the Saxon church, in north-east England, sold, this year, for

- £29,950.

The average price in the village is about £69,000.

Yet in 2005 the village’s average house price was £140,600.**

I’d like to explain what’s happened since 2005. Why there’s such a shocking divide between this village and, especially, the south. (Of the English regions, the lowest average prices are all northern: North-East £156,000, North-West £175,000, Yorkshire/Humberside £174,000.)

But I don’t have the resources – or the expertise.

I could take a stab at it. Changing tides of employment, the banking crisis, mis-sold mortgages, legacy of Thatcher’s council house sell-off. A repossession.

But I don’t really know.

It’s all about value, I realise – but whose? And why such vast discrepancies?

Heritage is a powerful force in modern, western lives. One reason why we have brown signs, to direct us to the art, the architecture, the heritage we value.

We found a Saxon church. We found a case of shocking inequality. They’re everywhere. They are our heritage, too.

It’s time some politicians took the long trek north and noticed the signs. There are plenty.

* Source: UK Government Office for National Statistics

** Source: Rightmove

Bewick’s wrens are among our favorites here in central Texas.

LikeLike

Small card on its way to you…

LikeLike

What a beautiful church. I got tingles across my skin looking at your photos.

It seems to be the way with villages that have little or no industry, infrastructure or proximity to something like that. Our own country village, where we hope to live one day, is such. Property prices had been modest & sales slow up to now… but since construction has begun the local section of a motorway and bypass house & rental prices and sales have increased to the benefit of some and detriment of others. We know when we live there our income prospects will be vastly lower than our city existence, some of our costs will be also but many others are static no matter where you reside and what you earn. I assume it would be the case for the Saxon church village also.

LikeLike

The church is very odd, and sad, but, yes, rather lovely. The region was heavily into coal mining and it has all but gone. The village is very poor and the ‘remodelling’ of the sixties was done badly. I just felt for the people who in the 80s were sold on the idea that buying the house they rented from the local council would make them better off. It’s nowhere near a main road, the nice pub is up for sale and the train station was closed not long ago… life signs not looking good. The north of England has never recovered from being the industrial bedrock of the UK. I wonder if it ever will.

LikeLike

Just spent a fruitless half hour rootling through suitcases and trunks full of old papers, photos and other nostalgia looking for a b&w photo of distant Bewick’s swans on a mountain lough in Donegal fifty years ago. I thought I’d done well having visited two Saxon churches, in Northamptonshire and Wiltshire, but an internet search tells me there are several more, and that yours was the one near Bishop Auckland. Must have a look next time I’m up that way. Thank you for the visit.

LikeLike

I suspect you went to Bradford-on-Avon to the Saxon church there? We used to live in a weaver’s cottage overlooking it – could see it from our bedroom window! J.Desmond Clark went to school across the valley and remembered the Ostler’s bell at the Swan Hotel in B-o-A. I went and bought some ‘memorabilia’ for him for Larry to give him from his old school while we were living there. There’s a church in Studland Bay, Dorset, that’s Saxon in origin and still very Norman too. I love Dorset. The one in the post is really different and has a slightly unnerving atmosphere.

LikeLike

Yes it was of course B-o-A. Thanks for your reminiscences – weaver’s cottage and the great JD Clark. Can’t say I know Dorset well but have often passed through it. When driving down from Portsmouth (off the ferry) to Cornwall we for many years made a little mid-journey detour down to Lyme Regis of literary fame. Have to stop off at Studland Bay next time. Thank you again.

LikeLike