The old Coca Cola chiller was a solid red beast of a thing. No see-through door on the side – no door at all – just a lid on the top.

It hadn’t worked for years, what with it being paraffin-fuelled and no-one knowing how to start it. But it kept our nets of fat avocados and glossy ripe tomatoes safe.

Safe from rodents, mongooses, baboons – anything wild with an interest in nibbling human-destined food.

The fridge stood under a canvas awning attached to a caravan. Which the Americans among our volunteers called a trailer.

It was one of those volunteers, Fred, over seventy and fully recovered – we hoped – from a bypass operation, who got the old metal cabinet chilled out again.

For what seemed like hours Fred lay on his stomach, after carefully pouring in paraffin. The paraffin itself had come from the nearest petrol station, an hour-or-so’s drive from our wildlife-reserve base, below the mountains bordering Mozambique.

It was a tricky business, lighting the flame, getting the refrigerant moving, but he did it.

We kept it up for a while after he left – the volunteers only stayed for two week stints – but then it lapsed and went back to being a food store. Which was fine by me.

Being fine by me was important. Because I was in charge of the food. Of cooking. Of catering.

At one stage, that summer, I had 24 people to feed.

I say ‘I’ – but I was lucky to have the help of Dudu. A ‘maid’ in the parlance of the time and place, she was a trained primary school teacher.

Thanks to Dudu I learned how to use the stove – an open fire. A large open fire.

No control knobs. Just a shovel, a cast-iron witch’s cauldron, a long spoon – and a red face.

There was also a ‘braai’ area – for men will always be men and want to flip meat. But banish images of sleek steel and aluminium. This was a stolid concrete block, with a recess in the top, over which a grate could be laid.

Embers from the main fire would be shovelled onto it and beastburgers – made from minced, culled wildebeest or, at a pinch, impala – grilled almost to extinction.

They tasted great with those glossy ripe tomatoes, sliced. On bread rolls brought from Mbabane, several hours’ drive away, stored in plastic bags.

We also used the braai to boil kettles in the morning – and hard-boil eggs for lunch.

The cold, scraped-out ashes formed a heap near a place we all liked to sit at the edge of the escarpment on which our camp was perched. It had tremendous views.

At breakfast, as the steam from tin mugs of tea or Ricoffy rose to wet our noses, we could watch impala or zebra roaming.

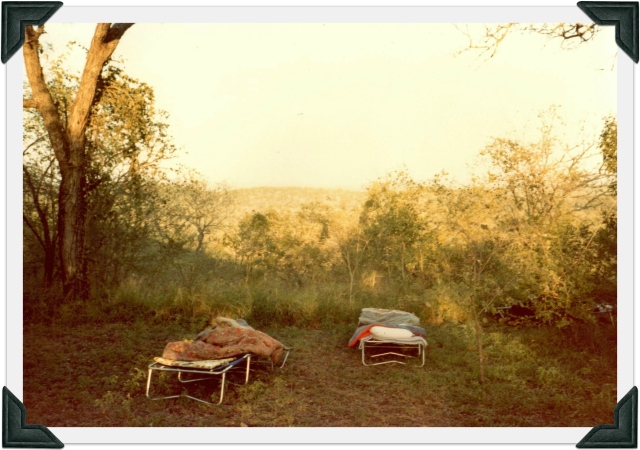

I offer this only so you can see the view from the campsite, looking down to what we called ‘cocktail rock. The man on the right is the one I arrived with and the woman to his left was a friend of mine from Boston who later married him – so, all’s well that ends well, eh?

Under the massed stars of chilly nights, it was close to the fire.

It was after dinner and after dark, as I watched the living fairy lights – my first fireflies – that the rodents came.

They weren’t as scary under milky-way skies as in suburban world. But still, they were large, furry creatures and we slept on sun loungers, close to the ground.

I tried not to think about them as I snuggled into my sleeping bag, under the plastic sheet which kept off the heavy dew, on top of the sleeping pad which insulated the lounger against the chill night air.

Each morning, my pillow wet around the dry imprint of my head, I was up before everyone else. Except Dudu.

Our first task was to resurrect the fire to boil kettles. Water was piped up in great long hoses from a railway siding on the other side of the escarpment. There steam trains stopped for refills on their way to and from Mozambique.

For hot water, there was a separate pipe going to this oil drum which was then heated over a fire. We bathed in tin baths on a ledge overlooking the bush below. Baboons stole our soap if we left it out

The water was treated, safe to drink – or so we were told. I’m still here, so perhaps it was.

While Dudu tended the fires, I’d decide on breakfast.

Everyone made their own toast. Peanut butter was popular. There were eggs – but since we had them hard-boiled with our packed lunches, the day often began with a liberal serving of hot baked beans.

We made sandwiches for lunch. Packed cheese triangles and flasks of hot water – yes, hot – for drinks.

When the others left, I often went with them, to dig, or explore.

Flames, smoke – not good inside a Land Rover we jumped out pretty damn quickly & the prof used tape to isolate the offending wires so we could drive on…

The prof & I centre,inside the cave, ‘digging’ (can’t remember names of the other 2, sadly) & getting on famously – no idea where the guy I arrived in Swaziland was at this point! Ahem.

But sometimes I stayed back. Watched in awful fascination as huge, seething hornets made great mud nests.

I helped Dudu with the dishes. Read, sunbathed, slept.

Shredded hard white cabbage and carrots for the evening salad, served in a washing-up bowl.

Chopped tomatoes for the guacamole a certain young American (now prof) would make as our evening snack. Alternating days with sardines and Tabasco on crunchy Provita biscuits.

I learned a little Siswati from Dudu, who laughed like a drain at my pronunciation.

And then it all changed.

I’ve written before about my hasty, ignominious departure.

I was exiled here at Jenny’s place, a farm, and occasionally a visitor like the prof-in-the-making would pop by – it wasn’t all bad!

But what about Dudu’s departure?

She had worked and lived with us privileged western folk for a few months. But we had houses – bricks and mortar, stone and wood – waiting for us when we ended our dalliance with ‘wild’ bush life.

She lived in a straw hut. And straw huts are vulnerable to lightning. Which is how Dudu died.

Much later, when I returned to that campsite, memories of my earlier banishment conveniently brushed into the ash pile, I missed her.

I missed her giggle, hidden behind her hand. Her slow and steady pace. Her amusement at my ineptitude.

I see her face still. And it makes me smile.

She was one like so many women, working so hard, living in huts, carrying water for miles, with no electricity. Cooking with lung-clogging smoke over open fires.

But that’s not a thirty-year-old memory. It’s still reality in large parts of many African countries.

And the picture I bought in a friend’s shop – Tishweshwe – in Malkerns, all those years ago, has a powerful, seemingly eternal message.

Its title:

Why do women carry such heavy burdens?

The title, Why do women carry such heavy burdens?, in pencil, has faded, unlike the reality of such backbreaking chores for women all over Africa

Lots of memories here ! How different are the expectations of different communities !

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is ASTONISHING. I got so swept up in your extraordinary writing that your matter-of-fact description of Dudu’s death hit me like a gut punch. We who are used to faucets that deliver clean water and who don’t have to protect our food from baboons or rodents have no idea how difficult and fragile life can be for so many millions around the globe. And yet you’ve shown us so much beauty here too! Thank you so much for sharing this marvelous, transportive piece. It’s likely the best thing I’ll read all week.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Aw Heide you have made my day, thank you! I am sorry I haven’t been over to look at your recent posts – it’s been a very erratic few weeks and I am hoping to catch up soon, starting…. now! I must see Paris in snow.

Yes, poor Dudu, she was unlucky in love too, so sad.

Thank you again, you are so kind 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I am doubly heartbroken to hear Dudu was unlucky in love, too. It’s difficult to understand sometimes why life is so hard on the good people. Still, I’m grateful you’re sharing a bit of her story here — and yours, too. It’s rare that I have such an immediate visceral response, but this morning when I read your post I felt as if I’d time-traveled with you to the past. Beautiful, beautiful writing.

LikeLike

Very well done! (I am delighted you had time to post this after your long walk yesterday!!) I love this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

🙂 More of that walk anon …

LikeLike

How vividly you’ve recounted these memories! I enjoyed this very much, as well as the short piece on being banished. The anxiety in that piece was clear. But I’m still curious about why you were banished. Perhaps I missed that, or it will be in another post sometime.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much Miz B. It was a story I told a while ago in a series of posts and actually pulled it together as a page – so if you are interested, go to the banner of my site across the top below the picture on the main page – there’s a link to, ‘Swaziland’. As it says, it was a story which changed my life forever and the banishment was one important part of it but not the most important! And it is only now that I have a decent scanner for old pictures which have seen the light of day for the first time in public. Very glad you enjoyed it. Thank you for reading both posts!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Isn’t it wonderful to look back on such big memories? And isn’t it a wonder when we look at other lives and realise that we have survived into (nearly) old age? So many didn’t. Still don’t. I really enjoyed the look into this past adventure in your life… and aren’t we grateful that the photos we take today by digital means will hold the colour and clarity a bit better than film? They probably can’t improve on the memories, though. That final print that you have is astounding. Why, indeed? x

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Ardsy – yes, we have been lucky by accident of birth – I always think this when I see women digging in riverbeds in parts of Zambia during the dry season for water to do their washing and carry in containers – plastic ones now – home, or carrying vast bundles of wood on their heads to make fire. I had two illnesses as a child which could have killed me – would have, had I been in rural Africa I am almost certain.

The pictures – well, to be honest, I was thrilled att eh scans – hd I kept the pictures more carefully they would have been even better but the colours that came through and the detail really amazed e. It was a cheap click and snap camera – probably a Kodak Instamatic or some such! The better pictures – like the one of me stirring the cauldron – were taken by others. 😉

I love the print – and to add to the wonder – it was done by a Swazi…. MAN!

LikeLiked by 1 person

We enjoyed seeing these pictures for the first time!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Perhaps the Me Too campaigners could spare a thought for the daily exploitation of women without options…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very good point, Helen. Hope all is well with you…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, things are on the up after the chilly trip to England…

LikeLiked by 1 person

https://wordpress.com/post/bbctown.wordpress.com/21

LikeLike