Imagine a human chain of sixteen and a half thousand people, mostly barefoot and carrying heavy burdens – sixty pounds, twenty seven kilos – on their heads. Some pulling carts.

Walking up to fifteen miles a day under the searing glare of the tropical sun, or in the sweltering heat of the rainy seasons. Feet grabbed by black, grasping cotton mud or floundering in soft, hindering sand.

Clambering rocky escarpments, pushing through jungles, wading rivers. Transporting essential supplies to a thousand other people, hundreds of miles away.

Those 16,500 humans were what it took to transport just one day’s supply of food to the British front line in ‘East Africa’ in 1916.

Fourteen thousand of those men and women – carriers, porters or ‘tenga tenga’ – carried food for the column itself. Only two and half thousand bore supplies for the troops.

Many of these people died, serving a cause which was not theirs. Sometimes willingly, for decent pay, sometime the reverse. Falling as much to disease as injury, like the troops they supplied.

They were not the only ones. This was just one chain in a very long series of chains on the British side. The Germans depended on 350,000 human carriers.*

And yet these people are largely un-commemorated. As, indeed, is the whole ‘East African’ action of World War I.

I put ‘East Africa’ in inverted commas because my first brush with its legacy came in South Central Africa – Zambia to be precise. There I saw a small – and not very visible – memorial on a roundabout in a small – and not very visited – town.

But this week, on 25 November 2018, that town will be busy. Possibly busier than it has ever been since the end of World War I.

Because many dignitaries, including British High Commissioner, Fergus Cochrane Dyet and General Lord David Richards, of Sierra Leone fame, will converge on that small town, Mbala.

The Great North Road, Zambia’s main route north to Tanzania, runs through Mbala and yet the tarmac peters out as it approaches the border (or did when I was last there, en route to Kalambo Falls).

It is a long, long way from any city, never mind Ireland, and to this day the logistics of visiting are far from easy (especially if you travel from South Luangwa up the escarpment as we did in 2006).

In 1914 Tanzania was German East Africa and Zambia was Northern Rhodesia – and there lies the crux of it. German one side of the border, British the other.

It was Mbala, then called Abercorn, that saw the final surrender, the other end and other ending – of the First World War.

Taken from a website devoted to 1950s & 1960s Northern Rhodesia/Zambia, posted by Amanda Parkyn this view of Abercorn shows the main road stretching up from the left crossing the watercourse fringed by mbala palms – which provided the new name- & the Tanzanian hills in the distance.

It had widely been assumed that the colonies in East and Southern Africa would not join hostilities, but Colonel Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck (a friend, by-the-by, of Karen Blixen) had other ideas.

German attacks on Abercorn and Fife in Northern Rhodesia and Karonga in Nyasaland (Malawi) made sitting out the war impossible.

Germany at war had visions of extending its colonial rule over Portuguese- and Belgian-claimed territories, to make a vast ‘Mittelafrika.’

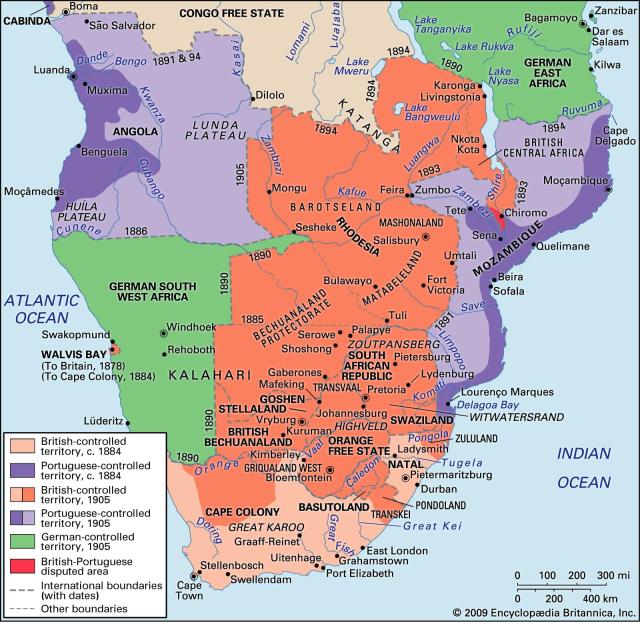

Map of colonial southern Africa in 1905, from Encyclopedia Britannica online

In German East Africa, von Lettow-Vorbeck, Commander of the Schutztruppe (the Germany colonial army, Kaiserliche Schutztruppe für Deutsch-Ostafrika) already had a force of trained, disciplined troops, askaris, at his disposal.

He also had a network of telegraph and heliograph (signalling with mirrors using sunlight) stations, which enabled him to coordinate his forces and move them around swiftly and effectively.

Northern Rhodesia had no such infrastructure.

It began badly for Britain. But she had an Empire to draw on – and allies.

The British South Africa Company, BSAC, which administered Northern Rhodesia, was not allowed to raise an army, though it had a police force trained on military lines – with its headquarters in Livingstone, over 700 miles (more than 1000 kilometres) away.

Abercorn was the northernmost town of BSAC-administered territory, a massive expanse of land stretching from South Africa to Tanzania, bordered by Portuguese, German and Belgian colonial territories.

One of the reasons such a vast expanse of territory was handed over to a company to run was to delegate responsibility (and avoid the cost) for developing a transport infrastructure.

For commerce to prosper, for ‘government’ to be imposed and order maintained, railways and roads were a prerequisite.

But commercial priorities proved a weakness in time of war. The railways had gone no further than commerce necessitated. No commercial justification, no railway.

Abercorn was more than 600 miles (1000 kilometres) from the nearest usable railway line (at Broken Hill, now Kabwe, famous for the discovery of ‘Broken Hill’ man).

There were no roads suitable for an army’s mechanical vehicles, whether steam or petrol powered – and no supplies of fuel.

In August 1914, the War Office in London delegated this ‘other end’ of the war, in East Africa, to the India Office, who sent in Indian Expeditionary Force B.

They were joined by the King’s African Rifles, comprising soldiers from across British territories in East Africa, including modern-day Kenya, Uganda and Sudan. Other British colonial forces came from the nations that are now South Africa, Malawi, Nigeria, Ghana, Gambia and Zimbabwe. Troops even came from the West Indies. And of course, Britain itself.

Belgian and Portuguese allies then joined the fray, from the Congo and Mozambique.

The Germans, though a much smaller force, had their highly skilled, disciplined army of askaris, well trained in bush warfare and skilled at guerrilla tactics. Their aim was to keep the enemy on the run and constantly draw in more troops in to hinder the British war effort on the Western Front.

It was a gruelling war.

The territory covered was huge, 750,000 square miles, an area three times the size of the German Reich. There were some pitched battles, but most of the action was by isolated columns of men, moving at times through elephant grass so tall that, while they could not be seen, they themselves could not see.

It was very different from the trench warfare of the Western Front.

Conditions were atrocious.

Lorry driver W.W. Campbell wrote of conditions in German East Africa:

‘Distressed and depressed beyond measure, we felt that death and ugliness lurked everywhere. It was in the air we breathed, the water we drank, the sun that warmed our bodies; it crawled on the ground, dropped heavily from rain-sodden trees, hung suspended in the humid, reeking atmosphere. Every living thing went in fear of its life, or turned upon another in self-preservation. Human life itself was an embodiment of ignorance and suspicion. It permeated our very souls, turned bright thoughts into dark, and made one long for the fate that he feared.’

[from ‘Forged in the Great War‘ by J-B Gewald, originally cited in Byron Farwell, The Great War in Africa: 1914-1918 p 274]

As well as the human enemy, there was the natural world to contend with, the lions, snakes, elephants, hippos, tsetse flies, mosquitoes.

Disease was rife: not just the debilitating and often fatal malaria, but sleeping sickness, meningitis, smallpox, dysentery, pneumonia – and as the war drew to an end, that devastating Western import, Spanish influenza.

The tsetse flies meant death to pack animals, hence the need for so many humans to take their place.

And their absence took its toll on the civilian population. They were not at home, raising crops tending to animals. The disruption to life across the vast territories affected was immense.

It was as if a vast plague of locusts and disease moved around, ravaging the whole region for the four years of the war. And when the fighting stopped, the angel of death flew in, spreading deadly influenza.

The abandoned fields, the ruined crops, the starving men, women and children. It hardly bears thinking about.

So far from Sarajevo.

So far from Tipperary.

Yes, Tipperary mbali sana, sana – Tipperary, very, very far – was apparently a marching song of the King’s African Rifles. Fighting for a cause they probably could not comprehend (did anyone?) in a war which was not of their making.

And I somehow doubt that any of the native soldiers’ hearts lay in Ireland.

A Zambian woman once exclaimed, when I said I’d been to Mbala, ‘Ah! How can that be? I am Zambian, it is very far away.’

Indeed.

There is so much more to say about this smaller ‘great’ war, about its human costs, about its political implications, about its significance, about its causes, but I’ve already well overrun my usual allotted space.

And so, to that other ending, of that other end of that terrible, ‘Great’ War.

As the last battle ended at Chambeshi Bridge, on 14 November 1918, General von Lettow-Vorbeck received the news that the Armistice had been signed in Europe. And the news he could hardly believe – Germany had been defeated.

Memorial at the site of Chambeshi Bridge. It reads: “On this spot at 7.30 am on Thursday 14th November 1918, General von Lettow-Vorbeck, commanding the German forces in East Africa, heard from Mr Hector Croad, then District Commissioner Kasama, of the signing of the Armistice by the German government, which provided for the unconditional evacuation of all German forces from East Africa”. A second plaque in Bemba ends with the words: “Twapela umuchinshi kuli bonse abashipa abalwile mu nkondo iyi” – we honour all brave soldiers in this war.

Image By Carrol Fleming – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

On 25 November General von Lettow-Vorbeck surrendered to Britain’s General W.F.S. Edwards, at Mbala.

The surrender to the British by General Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck at Abercorn, now Mbala, Northern Rhodesia, now Zambia, as seen by an anonymous African artist. Picture held by the National Museum of Tanzania

My thoughts on 25 November will be with the vast numbers of porters who lie buried, forgotten, their graves unmarked.

At least, in 2018, a few more people, thanks to a few tenacious historians, will remember them – and hope that they might rest in peace.

*Statistics taken from Edward Paice’s very readable online article, ‘How the Great War Razed Africa,’ published by the Africa Research Institute, which contains maps, illustrations, a very good bibliography and more detail than I could include here.

It is impossible to condense such a vast undertaking in such a short post and I am sure I have made mistakes. I can only apologise. Here are some better informed sources which I consulted, along with the above:

An excellent, readable, thought-provoking analysis of how the war was managed and what the war meant for government of the future British Protectorate of Northern Rhodesia:

Forged in the Great War: People, Transport, and Labour, the establishment of Colonial Rule in Zambia 1890-1920 by Jan-Bart Gewald

A good, personal, short introduction:

A Bloody Tale Best Ignored, by Richard Sneyd, for The Centre for Hidden Histories:

A very detailed but concise account of the early stages of the war in East Africa with pictures and sources:

This book cropped up again and again (and was well reviewed by novelist William Boyd whose book The Ice Cream Wars was set in the context of this conflict):

Tip and Run: the Untold Tragedy of the Great War in Africa, by Edward Paice

I learned a lot, thank you.

L

LikeLiked by 1 person

What an ambitious undertaking to try and tell so much history in a blog post. You certainly opened my eyes to this lesser known chapter of history. Well done!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Phew, at least one unrelated (to me I mean) human read it! Thanks, it was a bit ambitious…

LikeLiked by 1 person

This is a side of WWI that I knew nothing about. Thanks for writing about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome. For the first time I actually felt like I had done something worthwhile with my blog (then someone related to me told me it ‘went on’!!!) Sigh. But it is a big big story. Shamefully neglected.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You can’t please ’em all. Don’t try. I wouldn’t have wanted it any shorter.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It is shameful that we (or should I say I?) know so little about this ‘other’ WWI. Thank you for an enlightening and well-researched blog. Is Africa ever mentioned at Armistice Day events here I wonder? Or on 25th November in this country?

LikeLiked by 2 people

I know, and no, it’s not just you. Even Larry and I who’ve spent so much time in Zambia, other southern African countries knew nothing about this other than seeing the rather pathetic war memorials. Apparently the input of African troops is now mentioned but not the actual ‘war’. Shameful indeed.

LikeLike

A brilliant piece. Very informative of a little known part of WW1 history.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, glad you found it interesting. It’s not been a popular read but I feel I have done at least a little bit now to set the record straight.

LikeLike

WordPress can be a bit of a desert I’m afraid – pour your heart and soul all week into a piece and you get a couple of views – been there. I’m enjoying following you anyway.

All the best!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you!

LikeLike

Thank you for writing this. It was I who put together the whole commemorative event (with much planning over a two year period) wand it began with a visit to the Chambeshi site on 14 November 2018 at 07:30 where we came across some German travelers by chance assembling to remember things from their perspective. The godson of the African who carried white flag 100 years earlier with Hector Croad was able to join us – Charlie Harvey. The Zambian authorities were kind enough to let the memorial take place, and then began a series of re-enactments over a period of two weeks, including a battle between “British and German” troops televisied for Zambian TV, culminating in the colourful parade on 25 November at 12:00 – remembering the war in Africa lasted 2 weeks and 2 hours longer than it did in Europe given the time difference. I commend the Zambian people as a whole for the enthusiastic support for the idea which was carried off with near perfection. The grandson of General von Lettow Vorbeck, Graff Casper zu Rantzau, was able to join us despite the protestations of the German Government in Berlin over his attendance. Prince Harry had received an invitation to be at the event but in the event arrived in Zambia a day later. General the Lord Richards was most gracious to attend on behalf of the British Armed Forces and the High Commissioner on behalf of the British Government. The German Ambassador also present among others. His Excellency the President of Zambia insisted that the grandson of General von Lettow Vorbeck and General Richards sit next to him during the event which gave credence to all the time and effort put in to organising everything. Memorials to the Africans and settlers alike within Zambia are slowly being renovated with funds raised from ex British military individuals and other interested parties, and the main Abercorn Memorial at Mbala by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission. The incredible stories of these brave service and civilian personnel are being uncovered and retold to younger generations in Zambia.

Perhaps I could add this about Africa and World War One: It is worth remembering that the 2 minutes silence acknowledged around the world was in fact begun in Africa. The practice of the Remembrance Sunday silence originates in Cape Town, South Africa, where there was a two-minute silence initiated by the daily firing of the noon day gun on Signal Hill for a full year from 14 May 1918 to 14 May 1919, known as the Two Minute Silent Pause of Remembrance.

This was instituted by the then Cape Town Mayor, Sir Harry Hands, at the suggestion of councillor Robert Rutherford Brydone, on 14 May 1918, after receiving the news of the death of his son by gassing on 20 April.

Signalled by the firing of the Noon Gun on Signal Hill, one minute was a time of thanksgiving for those who had returned alive, the second minute was to remember the fallen. The city fell silent, a bugler sounded the Last Post, and the Reveille was played at the end of the pause. It was repeated daily for a full year. Newspapers described how trams, taxis and private vehicles stopped, pedestrians came to a halt and most men bared their heads. People stopped what they were doing at their places of work and sat or stood silently. This short official ceremony was a world first.

A correspondent in Cape Town cabled a description of the event to London. Within a few weeks Reuters’ agency in Cape Town received press cables from London stating that the ceremony had been adopted in two English provincial towns and later by others, including in Canada and Australia.

Sir Percy Fitzpatrick was impressed by what had happened and suggested through various channels to King George V that the 2 minute silence should be observed throughout the world and the King consented that the 2 minute silence would become part of the Remembrance Service on 11 November 1919 and each year after that.

On 11th November 1918 at 11:00 European time the Great War came to an end, officially at any rate. It was supposed to be the war which ended all wars. Sadly, it later became known as World War One. It lasted for 4 years, 3 months and 2 weeks involved over 50 countries and cost the lives of 9 million soldiers, 7 million civilians and most certainly a contributary factor to the outbreak of influenza around the world which killed between 50 and 100 million people.

However, the war in Africa continued and it is worth remembering now the role of Africa in the war because it was significant:

The first rifle shot of World War one was not fired in Europe but actually in West Africa on 7th August 1914 by L/Cpl Grunshi of the Gold Coast (now Ghana) Regiment. The German garrison in Togoland held out for just two weeks, when the campaign started on 9 August 1914 and it was over by 26 August 1914. The first campaign of the war was successfully concluded in Africa by African Regiments.

The first naval engagement between Germany and Britain was on Lake Nyasa, now Malawi, when Captain Rhoades sailed his naval craft, the HMS Gwendolen, back to his German counterpart’s harbour having heard of the out-break of the war first and blew holes in his vessel, the Hermann von Wissman, which was in bad form according the German, Captain Berndt, as it was still in dry dock at the time. He rowed out to confront Rhoades to question what he was doing since they had been drinking partners the night before. It transpired that news of the war had not reached him yet. Rhoades sat Berndt down with a whisky, explained the situation, then led away his angry prisoner of war into captivity.

The famous film “The African Queen” was based on a true story when Great Britain sent two small attack craft, HMS Mimi and HMS Toutou, to Cape Town on a ship and then up the railway line to put them on to Lake Tanganyika to challenge the Germans who had the Kingani, a larger vessel in command of the Lake. The two boats managed to capture the Kingani, renaming it the HMS Fifi.

The first major land campaign was successfully concluded with no British involvement at all when the South Africans and the Rhodesians secured victory in the German South West African Campaign. It began on 15 September 1914 and was over by 9 July 1915.

This country raised funds to assist Great Britain, and amongst them were the Angoni chiefs in the east contributing a princely sum of GBP32 and Sh1 at the time to help buy an aeroplane for the British Army. The Litunga from Barotseland thought it an honour to support King George V so raised GBP2,000 for the war effort as well and ordered his son who became Mwanawina III to march with 2,000 Lozi warriors northwards to be trained into Policemen and carriers in the defence of the territory.

The last airman to be shot down by the famous Baron von Richthofen, the Red Baron, was Second Lieutenant David Greswolde-Lewis, born and raised in Bulawayo, Southern Rhodesia.

A Victoria Cross was awarded to an Australian soldier, Lieutenant William Dartnell, in Kenya where he is buried.

There were 20 countries involved in the East Africa Campaign which finally ended in this country: Australia, Belgium, the Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo), Gambia, Germany, Gold Coast (now Ghana), India (& Pakistan), Kenya, Nyasaland (now Malawi), Mozambique, Nigeria, Portugal, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanganyika (now Tanzania), Uganda, Southern Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe) and Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia) and the United Kingdom.

Whilst the guns fell silent in Europe on 11th November they continued in Africa until 13th, when General von Lettow Vorbeck’s troops were about to cross the Chambeshi river in Northern Rhodesia and the last shot of the war was almost certainly fired by a Northern Rhodesian Policeman south of the river in response to the advancing German Askari firing on them at the rubber factory. The delivery of the news of the Armistice had been delayed at a town called Broken Hill, now Kabwe, when the inhabitants received it on 11th they had a such a party it was not until the 13th that they realised no-one had sent the official message forward. General von Lettow Vorbeck was given the news of the cessation of hostilities on the Western Front on that day, firstly from information taken from a captured dispatch rider, the last prisoner of World War One, a man called Eric Pullon a civilian, and then later that same day from a note sent forward through the British front lines by Lieutenant Davey and Sergeant Romsey of the Northern Rhodesia Police. The German General was planning to attack the rubber factory on the southern bank of the Chambeshi river the next morning.

So, at 07:30 on 14th November 1918 General von Lettow Vorbeck met with Hector Croad, the District Commissioner from Kasama, to be told that he would have to march to Abercorn, now Mbala, to lay down his arms in front of General Edwards. The man who carried the white flag to the meeting was Yoram Jia, an African originally from Nyasaland. Both Croad and Jia later worked on the Shiwa Ngandu estate made famous in the book The Africa House.

It took von Lettow 10 days to complete the journey and at 12:00 on 25th November 1918 in the pouring rain he began his unconditional evacuation from East Africa. General Edwards allowed von Lettow to keep his sword because of the honourable way he had conducted his campaign.

Given the time difference, the war in Africa lasted two weeks and two hours after the guns had fallen silent in Europe.

We remember the 78 settlers of this country including one lady, a Jewish lad and an American listed on the Livingstone memorial at the Victoria Falls, who left their homes and gave their lives for the cause.

We remember the 117 men of the Northern Rhodesia Police including an Australian who are listed on the police memorial in Livingstone town who died defending this country from invaders.

We remember Hector Croad buried in the Pioneer Cemetery in Mbala and Yoram Jia who carried the white flag on 14 November 1918 to bring the fighting in Africa to an end.

We remember the servicemen buried at Kansenshi in Ndola not only people from units in this country but also from the British South Africa Police, the Royal Navy, South African Forces and one from Belgium.

We also remember the German soldiers and their proud Askari who died and are buried in Africa.

We remember people like Private Beattie from the Northern Rhodesian Rifles who was buried in a grave at Chinsali in 1916, unmarked officially, a piece of African granite acting as his headstone because someone will not look upon him as a war casualty. His family mourned him nonetheless and his name is recorded on the official memorial panel in Hawick, Scotland.

We remember those affected by war like Captain Evans MC and bar, DCM, Russian Cross of St George 2nd Class, MID, from Abercorn, now Mbala, who after the war suffered from the demons which haunted him, called Ukutilimuka locally or more commonly today Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, and was the cause of him being stripped of his all his bravery awards in 1923.

We remember the 1,467 carriers from the Northern Province who died whilst serving in the British Army and the 433 who fell in this country for whom the Abercorn Memorial in Mbala is dedicated and where we in Zambia held our centenary commemoration on 25th November 2018.

We remember and acknowledge the over one million Africans who served in many roles during that war and in subsequent conflicts around the world.

LikeLike

This is really interesting Peter, thank you so much for taking the time to write it up for me and anyone else who might be interested. Have you written this lot up for publication? Where are you working now?

LikeLike

And I think you met my husband Larry Barham in a bar in Livingstone when he was with the then High Commissioner! Am going to email you would be great if we could keep in touch.

LikeLike