A trip to Bangweulu Swamps, Zambia, in the rainy season

A wet coming we had of it. The worst time of the year *

December 2006. Christmas, again.

‘Let’s do something different,’ we said. ‘Cancel the cake. Stuff the stockings. Forgo the pheasant.’

‘I know,’ says atheist-anthro-man, ‘why don’t we take a box of little plastic tubes to Africa, in the rainy season, then head into the swamps and get a load of people from the most reviled tribe in Zambia to spit into them for us.’

‘Yay. I’m up for that,’ I might have said. But probably didn’t.

Christmas Day arrives and finds us moping at Heathrow. Flying today was meant to be fun – quiet, good food, everyone friendly and full of cheer – but of course it’s British Airways, plus there’s been fog for three days and everyone is grumpy.

Things start looking up on Boxing Day. We arrive in Zambia to rain, but also sun. We pick up our Land Rover, with unaccustomed ease, and drive away in an optimistic bubble for our big Christmas adventure.

The Great North Road is my favourite main road in Zambia – not that there are too many – Great East, Great South… you get the idea. And we’re not talking motorways.

He’s driving carefully, well within the speed limit, when a policeman steps out from under a mango tree and waves us down. A ticket for not speeding. Do we want to pay here or drive back a couple of miles to the office?

We drive to the office, pay and get our certificate. Well, at least we had a choice, the official way and the other, cheaper one, but it’s not an auspicious start.

We recover, dust ourselves off and drive back down that hill at 80 km per hour below the limit.

Several hours later we pull into the sanctuary of the Forest Inn for the night. It’s usually a pleasure staying here, but things turn nasty as a group of young Zimbabwean farmers insult the polite, religious Zambian staff and re-enact things in the public rooms that should stay private. We intervene, they apologise, but the insults don’t stop. We keep a fan on all night to mask the noise and leave early next morning, a sour taste in our mouths that has nothing to do with breakfast.

We chug for yet more hours up the Great North Road, past lone women standing by the roadside, swathed in patterned cloths and babies, selling bowls full of bright red chanterelles that look for all the world like pots of poinsettias.

At last, turning right, we slither and squelch our way through wild, wet woodland to Mutinondo Wilderness.

It being Christmas, there’s no room for us at this isolated but popular ‘inn’, so they fix us up with a tent. Yes, I know, the rainy season. A tent.But it’s fun.

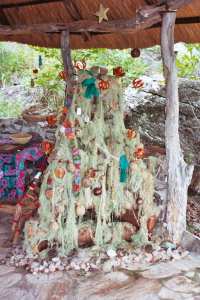

The Christmas tree’s unusual and our hosts are welcoming as ever.

I wake on the feast of the Holy Innocents (28th, my birthday) to a mug of tea in my tent and anthro-man’s gift of a local silver necklace. It’s been made right here and boasts not just a local amethyst but a couple of ancient trade beads. I wear it, for the journey. Well, why not?

I’m edgy. I can see in our hosts’ eyes that they aren’t quite sure about this trip, but they know us, know there’s nothing we can do now – except go.

It’s not raining as we set off. We make good time and soon we’re at our point of no return – a lodge famous for its bats. Here we pick up food and water to take to our destination. A tsetse fly bites my lip. There are none here, they say. Hmm.

Marjorie, a beautiful young woman who works here, is on her way home for a few days and we give her a lift. Although we nearly brain her – by accident – within just a few hours of meeting her, she doesn’t hold it against us. Just as well since she’s the grand-daughter of the tribal Chief we want to meet.

But I’m getting ahead of myself.

Next time – an innocent little detour off the track, onto the green, green grass, just half an hour into our epic – some might say barmy – journey

*after TS Eliot’s beautiful Christmas poem, ‘A Cold coming we had of it’.

Can you see where we’re going?

We’re on the kind of track we’re used to, here in Zambia – just about a vehicle’s width and peppered with rocks. Thing is, we’re usually here in the southern hemisphere winter – our summer. Then, it’s dry as a bone and rust-coloured dust trails follow wherever we go, you watch for big rocks or holes in the track and drive round them.

But now it’s been raining for weeks, the grass is a vivid, lush green – and we’re heading for the swamps. So, when anthro-man swerves to avoid . . .

Soowishhhh.

We’re up to our axles in soft, soft mud.

A little girl with big eyes appears outside my open window. She reaches in and touches my new necklace. Then she reaches up and touches my hair, shrieks and runs away. Maybe it was the green eyes.

Hooray for Marjorie. She recruits a local man who brings branches and sacks – and digs like a demon. He’s a teacher and his English is terrific.

Two hours later we’re back on track but running very late. A little haste seemed called for, but after we hit a massive hole – and nearly knock poor Marjorie out as she bounces off the roof – we take it a bit more steadily. After all, it’s only about a 60 kilometre drive. Three hours should do it, surely?

A couple of those three hours later – in the middle of the afternoon – we drop Marjorie at her village. The light’s already going.

I get out, shake various hands, say goodbye, then shove hard as the wheels spin. One foot sinks into mud, well over my ankle. Never mind. It doesn’t smell. Well, maybe just a bit – of fish.

Marjorie’s family said we should make it to the ‘island’ in two or three more hours. Neither of us wants to talk about it. But now the light is nearly gone.

‘Is it left here, do you think?’

‘Um, would you say this is “shortly after the settlement”?’

‘Depends where you think the settlement ends.’

‘If that was the settlement then I guess it’s – well, what do you think?’

Anthro-man hesitates but doesn’t stop.

‘It looks rather overgrown, doesn’t it?’

Now, back home in England, if you take a turn down a cul-de-sac in some strange industrial estate, in the dark, (I’m not saying I have, just imagining) you might feel a bit irate, a bit lost. A bit anxious, even. But if you stop to turn round you’re unlikely to sink into mud and be unable to get going again. It adds a certain tension to the experience. That and the lack of light.

So, I’m gripping the piece of paper with our directions as if my life depends on them. And the torch. And the guide book. As if that’s any use.

I’ve even stopped noticing the fishy-smelling mud.

We make a cautious turn, drive back at snail’s pace through what might just be the ‘settlement’ – a strip of forlorn-looking thatched mud-huts that are oddly empty.

We don’t see a single person.

Another slow turn. We start again, end up at the same place, drive further, turn round, come back.

So then – we take the left turn.

I shine my torch on the directions and screw up my courage – what little is left of it – to make a suggestion. One which turns out to be as useless as it is brave (given I’m a great big cissy coward.)

‘It says here there’s “a very basic community camp site”. Why don’t we sleep in the vehicle and wait till morning.’

He says nothing, just hunches further over the steering wheel.

‘We’re not even at the flood plain yet,’ I say in a feeble voice, not really wanting to be heard, ‘and you really don’t want to know what it says about driving across it.’

I realise I’m holding my breath . . .

Bonfire of the insanities

The track is overgrown with tall grass, but a vehicle definitely passed this way, once upon a time. That should be a comfort, but it isn’t.

I peer at the guide book in the yellow light of my torch and try to sound confident.

‘It should be along here somewhere. On the right.’

I doubt anything’s along here, actually. Much less a campsite. But at least we’re not sinking. Yet. Why did I read that story? Six months before they got the vehicle out – with a helicopter.

We’re not prepared for this. No sleeping bags. No blankets. We do have food and bottles of water but I haven’t drunk anything for hours now. I dread the thought of stopping the vehicle again and getting out to pee. Experiencing that sinking feeling for real.

Despair is gaining the upper hand when I spy the flicker of flames and a large fire – a veritable bonfire – illuminating a cluster of small grass huts.

Thank God!

It’s the campsite. Despite the look of the place, I feel relieved.

I should have known better.

We turn off the track and approach the fire.

That’s when we see them.

Several shapes appear behind the leaping flames. Men in dark clothing, wearing black Dunlops* and carrying big sticks. At least, that’s what I hope they are.

One man makes his way round to the front of the fire.

‘You cannot stay here.’

We’ve been in scrapes before in rural Zambia. People appear from nowhere to help, expecting nothing, happy with a lift, a handshake, a packet of biscuits. Thrilled if we have a Kwacha note or two to spare. So this is not looking good. Not good at all. In fact, it’s looking what you might call sinister.

‘We are lost,’ pleads anthro-man, ‘we need to stay the night.’

‘You cannot stay here. Where are you going?’

We tell him.

He waves an arm – no, he shakes it, as in fist – in the direction we were heading before we turned off.

‘Thirty minutes that way. Go straight. Keep going.’

We don’t really have much choice.

The tall grass disappears and our meagre headlights shine on flat ground – or is it a shallow lake? In the dim starlight we can just make out a causeway, slightly raised above ground level, the obvious way to drive across this floodplain.

‘It says not to take the causeway,’ I say, desperately wanting to take the high ground. ‘Too damaged, worse than crossing the swamp at this time of year.’

There, I said it, swamp.

I can hear the shoosssshhhhhh of the water, as the tyres roll on.

‘Aim for the tree,’ I say.

Bloody guide book. Puny headlights, star light – they’re not much use when you’re scanning a vast horizon for one solitary tree.

By now I’m beyond frightened, I’m terrified. We can’t stop. We’ve no idea where we’re going. Are we going in the right direction? Did that man tell the truth?

I clutch the guide book, the printout of directions and the torch as if rigor mortis has set in. I bite my top lip. Then my bottom lip.

Anthro-man grips the steering wheel as if his life depends on it, hunched over, head close to the windscreen, peering into the night.

What seems at first like a black cloud but is actually a wave of dark, moving forms appears to one side, rushing headlong towards us. It’s a vast herd of Black Lechwe antelopes, but we can’t stop. I cringe as if they’re going to hit us.

The herd parts and passes us, front and back, like a wave round a ship, as we make our slow way across their territory.

I wonder if we’ll ever be able to stop. We might end up in the Congo. It’s not very far away now.

It’s not a comforting thought.

*Wellingtons or gumboots

Rain, leaks and onions

The old Land Rover has old headlights. They’re not much use when you’re lost on a floodplain in the dark. Then you need floodlights, ha ha.

I don’t know why I said that. I’m far too scared to find it funny. But then–

‘Look, the water’s gone.’ Anthro-man points to the feeble glow of the lights on the ground. ‘It’s a hill!’

My heart beats faster. The vehicle climbs a minor incline that would scarcely pass muster as a hill anywhere else.

I hardly dare believe it.

‘There’s a gate,’ I say, then shine my torch on the hated guide book. ‘It says it’s the scout post. Do you think . . . ?’

He reaches out and puts a hand on mine. I shut my eyes. The relief is overwhelming and I fear for tears.

Two men in green uniforms rouse themselves from their lounging, surprised to find two white folks driving through their check point in the dark – and rain.

‘Can we drive from here to the camp,’ anthro-man asks, ‘is it safe, or do we need to take a canoe?’

Please, God, no!

‘Eh. You can drive. It is that way. Maybe ten, fifteen minutes.’

They return to lounging. I brace myself for more lake skimming.

Soon, despite the rain and the blurry swipes of the windscreen wipers, I pick out the lumpen shape of the camp, a bump on the near horizon.

Being able to see our destination does wonders for my morale. I sit up straight, worrying now about what we will find when we arrive, while anthro-man focuses on getting us there without sinking.

More nerve-wracking shooshing through shallow water brings us to another incline and three figures emerge, carrying lanterns, to wave us into a safe parking place.

Now we find out why no-one had come out to find us – they have no vehicle. These poor men are stuck here till someone drives out to fetch them.

A few minutes later and I’ve changed my muddy shoes and socks in our tent – an A-frame, with a bed in it. We wash our filthy hands in a basin then trudge across to the dining room, in the rain.

It’s not so much a shed as a tent with delusions of grandeur, the floor like a spongy cheap marquee’s floor. A long, dark dining table and chairs sits to one side and old-fashioned sideboards line the other. We sit, then have to move to avoid the leak.

One man sets the table, bring out glasses, napkins, place mats, all the trimmings of an old-fashioned restaurant, from the old-fashioned sideboards. Through the open door a kitchen range is visible, a roaring fire, burning bright.

The chef brings chicken à la King. Not a gourmet’s feast, but one of the best birthday meals I’ve ever had. Hot food. Red wine, even.

And safety.

We retire to bed, drained of the power of speech and desperate to sleep.

As we pull up the sheet and the heavy Zambian blanket, an odour of – I convince myself – onion arises.

‘They probably dry the blankets by the kitchen range,’ I think I say aloud. Or maybe I’m asleep already. Whatever, there’s no reply.

The rain drums on the tent but I don’t give a damn if it’s leaking. At least it’s not sinking.

Flies, rain and an intimation of tribal tribulations

I wake to clanging and crashing. Turns out it’s our shower, a bucket pulled from the well, the water heated on the range. Feels odd, a bucket shower in the rain.

Two pairs of black Dunlops have appeared by the tent opening. I turn mine upside down, shake them to dislodge anything nasty, then step out and take my first look at the landscape. It’s flat, wet and green. Perky stems of yellow-hot-poker alleviate the monotony.

Two pairs of black Dunlops have appeared by the tent opening. I turn mine upside down, shake them to dislodge anything nasty, then step out and take my first look at the landscape. It’s flat, wet and green. Perky stems of yellow-hot-poker alleviate the monotony.

I’m quite enjoying breakfast, despite the odd tasting tea (because of the odd tasting water), when we hit the first major worry of the day.

They have no idea why we’re here.

‘But the man from the bat place said everything would be ready for us,’ says anthro-man.

[I’m not surprised. I haven’t met the bat man yet, that pleasure lies in store, but he did say there’d be no problem driving here, this rainy time of year. His star’s not riding high with me, so far.]

So. We don’t have the Chief’s permission to do the DNA sampling. There won’t be thirty people from the BaTwa tribe queuing up to spit into little tubes. Not today, not tomorrow, not the next day. And that’s the reason we’re here – to ask people to spit into little tubes so other people in Germany can analyse it and tell anthro-man what their origins might be.

We have three days to make it happen. Bit like Time Team. But more serious. And without a TV crew.

Edwin, a kind, gentle and religious man, volunteers to help us.

Our first task is to track down Marjorie – her grandfather’s the Chief whose permission we need. We’ve brought him a blue and white teapot and mugs from Lewis’s of Liverpool. We should have brought tea and sugar, too, I realise. Too late.

The Land Rover proves reluctant, but eventually we cajole her out onto the flood plains again. In the welcome daylight (and less welcome rain) I spot a couple of tiny brick-built thatched huts, each just one square room, with wood smoke rising from their roofs.

Edwin’s family – wife, daughter and very new baby – live in one of these cramped, smoky dwellings. He’s anxious. Their last baby died of malaria.

We follow submerged tyre tracks across the plain. It’s easier at first by day, but soon it’s hard to see through the black veil covering the windows. It’s made of flies.  They ride with the herds of Black Lechwe which cantered around us last night. And now, with us.

They ride with the herds of Black Lechwe which cantered around us last night. And now, with us.

We’re approaching the first settlement when we see a small-ish man, with a crumpled-looking face, wearing an anorak, hat and the requisite Dunlops.

Edwin tells us to stop. This man is both useful and necessary. He’s a community leader and – we are told – a member of the BaTwa tribe. But he denies it.

Hmmm. We explain what we’re here for. He shakes his head.

All in all, it’s not looking good.

But he promises to tell the community, to seek volunteers, to meet us with them next day – if the Chief approves.

Things start looking up after that. We find Marjorie, visit Chief Chiundaponde and his wife and hand over the gifts. The Chief offers us his retainer’s help – he’ll come back with us, stay the night in the settlement and help recruit support.

We stop by the retainer’s village so he can pick up his things. My need to pee becomes too strong to ignore (that tea). I have no choice but to brave the village latrine, up a slope beyond the huts. My clumsy boots sink into the mud either side of the hole. I try and scuff it up to repair the damage and make it worse.

I leave feeling guilty – and clumsy. But at least I won’t be back – and it’s another milestone. Me, the sensitive girl from the suburbs. Using a communal long-drop loo. In a traditional African village. In the swamps of northern Zambia. In the rain.

It feels like someone else’s life.

But it’s not.

There was an old woman who swallowed a fly (well, not that old, actually)

It’s not the best way to start a day. I really don’t recommend it. In fact I’m trying to avoid writing about it. But I can’t.

We’re driving round a bend between two huts. I open the window and say something – I’ve no idea what, the fly puts everything out of my mind.

It tastes vile. Imagine concentrated greenness with added bitterness. Lots of bitterness. So bitter it feels like your mouth has dried up and your throat has shut. I try to spit it out but it’s too late. I drink water but it makes no difference to the hideousness of the taste. Eeeurgh.

We’re slithering and sliding, on and off the track. For twenty three hours it’s been raining non-stop. Crossing the floodplain was scary, even Edwin seemed anxious.

We reach a little group of huts that the village built for eco-tourists. I don’t know how many pass this way but it doesn’t look like it’s changed their fortunes. Who suggested it? They must be disappointed. Angry, even. I put it out of my mind.

Contrary to custom, I’m offered a chair at the table with the men. Through the ‘window’ – a hole in the side of the hut – I watch a woman drag a tree trunk across the space in front of us to make a fire.

I have a feeling the sampling’s not going to take us long. Despite the best endeavours of the Chief’s retainer there’s no queue of volunteers.

There are ethical guidelines for taking DNA samples. We follow them. I ask the first man’s tribe but not his name. ‘Bemba,’ he says. Or maybe, ‘Tonga.’

It doesn’t matter. It’s not BaTwa.

Four samples later and only one admits to BaTwa.

Now, please don’t be annoyed at what I’m about to write – I’m just reporting what I hear.

Ask Zambians about the BaTwa and they usually laugh. Often they hide their faces with their hands. So then you ask, why?

‘Ah! They are dirty.’ ‘Thieving.’ ‘They sleep with their sisters.’

It’s no surprise, then, that even among their friends and neighbours these people won’t admit what’s plainly true – they’re from the most despised tribe in the country.

Despondency sets in. Four samples and we need thirty.

Community leader takes anthro-man outside. They come back looking serious. Anthro-man passes me a note.

‘Don’t use the term BaTwa.’

I can see he’s reaching the end of his tether.

Outside the woman’s been scrubbing dishes in a bucket of water. Now she’s cooking something on the fire. I have a feeling it’s for us. I hope it’s not mice, or chicken gizzards – Zambian delicacies I haven’t yet tried.

With relief I see it’s just rice. We each receive a tin plate and a bowl of sugar’s passed around to sprinkle on it. There’s weak tea with strong water – not whisky, just the strong-tasting water from the well (that we shouldn’t really drink).

I eat. I drink. I worry. One of the tubes of spit looks really bad, sort of grey.

We make our farewells and Edwin leads us back across the lake that’s growing on the floodplain. He wants us to visit his wife and baby.

I step into the tiny hut and my worries evaporate. This woman gave birth a few days ago. Their only furniture is a rudimentary bed and plain wooden bench. A knotted mosquito net hangs from the thatch. Mrs Edwin’s smile is radiant, she’s proud of her new infant – and her daughter.

As we make to leave I remember we have a packet of biscuits. I hand the lemon creams to Edwin’s daughter. She screams with delight.

I’m ashamed of myself. To have so much – and fear so much.

That night we agree it can’t go on. We’re not going to succeed in two – or three – or four more days.

And still the rain falls.

A necklace, a paperclip, some rather unwelcome fireworks

Breakfast. Our last cup of tea made with well water. It tastes as if chrysanthemums have died in it. But it’s not as bad as that fly.

The men looked after us well and seem sad we’re leaving early. But if it keeps on raining we’ll be stranded.

I’ve become kind of used to the waterlogged expanse of green, the lone fisherman, the bundles of shiny fish. But I won’t miss the wet tent, smelly blanket – or the flies.

Anthro-man’s ill, but has to drive. I’m not used to handling these conditions – and it’s no time to learn.

Part way across the floodplain the windscreen wiper drops off. On the driver’s side. It lands in the groove by the windscreen. We pray it stays there, negotiate a slow, wide turn and drive back.

Anthro-man unbends a paperclip, wiggles it through the wiper. I cut a length of leather from my necklace of wooden beads and tie it through the gaps. It works, for now.

The plain’s quite deeply flooded, the slow pace torture. Rigid with fear, I stare through the streaky windscreen, willing the wiper to stay in place.

The tracks on the other side have worsened overnight. We struggle to keep going forward, sliding on and off the good bits. At Marjorie’s hut we slow to a nervous halt.

Marjorie, our good luck charm, jumps in, the villagers push us off.

Soon we’re approaching a dambo – a place that’s wet when everything else is dry. A causeway runs across it and a rudimentary ‘bridge’ spans the middle.

A stream’s running down the track we’re on.

Two little boys appear alongside us, shouting. We wave and ignore them.

‘Stop, please,’ says Marjorie.

I’m cross. It’s really bad timing. But she winds down the window, chats to the boys.

‘The bridge is broken,’ she says, ‘they will go ahead and show where you must not go.’

Sorry, Marjorie. Sorry, boys.

The youngsters wade in, stand either side of the ‘bridge’ and we see the great gap in the right hand side. Water pours over it like a cataract.

We inch along the causeway to the bridge. What’s left is barely as wide as the vehicle.

Our rear wheels start to leave us, going right, sliding over the edge, into the dambo.

How do we get out if we sink? Are there crocodiles? We’ll get Bilharzia . . .

Our front wheels grasp at stones beneath the mud. The rear creeps back onto the causeway. The little boys run after us shouting and smiling.

‘Biscuits!’ I remember. ‘There’s one packet left. Marjorie, can you tell them to share them?’

One boy grabs the packet through my open window and runs off, laughing at the other.

Boys.

It’s desolate now. We drive for hours, and hours seeing no people, no dwellings, just trees. And rain.

We stop once, on a patch of rocky ground, to pee. I manage to choose a spot by a poisonous plant. Great itchy welts appear on my thigh.

We’re nearing the place where Livingstone died when the torrent of water grows fierce. We’re taking it slowly because of the potholes – but then the vehicle slides to one side.

The water’s pushing us off the track. Anthro-man revs. The wheels spin. He revs some more but we carry on sliding sideways. I hardly dare breathe.

I’m getting ready to jump ship when the front wheels catch.

We lurch forward. I breathe again.

Eventually we arrive, in daylight, to a room with a roof and a bed. We order an early meal. Stagger over to the dining room hoping we don’t have to make conversation.

‘I’m sorry,’ nice woman says, ‘it’s New Year’s Eve, everyone’s eating together, later.’

Much later.

So we sit, later, round the table and finally meet the bat man, face to face. There’s one other man at the table. He puts me in mind of Hugh Hefner. Says he’s slept with a thousand Zambian women. Yeah.

I have instincts about people. We listen, avoid conversation, eat.

Exhausted, we drag our weary bodies to bed and lie in silence, seeking sleepy oblivion.

That’s when the fireworks start.

A crab, some washing and a tiny little miracle (well sort of)

A dry room, a cosy bed, a quick breakfast (avoiding bat man) and we’re on our way again. This time I’m driving. Anthro-man’s feeling really bad today. Dizzy, bad head, no appetite. Not like him at all.

The rain eases off as I reach the main road. Oh lovely Great North Road, you fabulous strip of tarmac!

A couple of hours later we take the turn off for Mutinondo Wilderness. The track pushes through dank woodland. Towering spikes of bright red flowers rise from the wet grass through dripping branches, reminding us it’s still the Christmas season. The track’s muddy, slippery, but manageable, even for me. No forceful streams, no rushing torrents.

We round a bend in the track and the pink hills of Mutinondo soar from the landscape, just for us. I’d like to think so, anyway.

It’s such a relief. I’m even resigned to the tent when – hooray – we’re told we have a room. It’s down the hill – and open on one side, as all but one of the rooms are here.

I should be intrepid after all these years of Zambia, but I have to admit it unnerves me, the lack of a door. Even a tent lets you shut out the world.

But I’m sure our mosquito nets will foil the lion attack that is (in my head) in the offing. Or perhaps I’ll just savage it with my girl-version-small Swiss army knife. I keep it under my pillow. . .

It’s all going well – clothes in for washing, warm water shower (well, not cold – you can’t have everything), comfortable lunch, afternoon rest, when it’s my turn to wither.

I feel ill. Really ill. Can’t drink. Can’t eat. Make it to the dining room, then turn back and follow the stream that’s tippling downhill to our room.

It’s raining like there’s no tomorrow. There might not be – that’s how I feel right now. I drape the mosquito net around the bed and lie down for the night.

Twelve hours later I feel as if a storm’s passed through. Through me, that is. I’ve tracked a weird feeling moving through my body and now I just feel sick. Very sick. I summon up all my strength and dress, sitting on the edge of the bed.  That’s when I see the crab, taking shelter in our room.

That’s when I see the crab, taking shelter in our room.

It’s too wet for crabs out there.

Anthro-man gets the Land Cruiser* out and goes for a drive. He’s scouting out some site or other – Later Stone Age, maybe. I’m too wiped out to consider it. When he returns we lay our washing out on the warm bonnet to dry in a brief rain-free spell.

I force down a dry bread roll. Anthro-man settles me in and we take the Great North Road south.

By now I’m sure you’re as tired of this trip as I am, but, bear with me – there’s one more, happy, experience before journey’s end.

There’s a place called Fringilla, not too many miles outside Zambia’s capital, Lusaka. It feels like the first (or last, depending on which way you’re going) homely house. Not that it’s a house – it’s a farm and a guest lodge. But when I see the sign, it just makes me – ahhh.

There’s a feel about it that’s wholesome, somehow. I guess it comes from the owner and staff. They practice the ‘love thy neighbour’ bit of the Christianity that they visibly – but not intrusively – espouse.

We drive in and order tea. I’m not sure I can drink it. We sit in cosy armchairs and I – presumably – look pale.

The nice man in charge makes a point of coming to welcome us – as usual. Asks where we’ve come from – and stops. He gives the enfeebled me a good hard look and then nods.

‘What you need is one of our own, hot, chicken pies, fresh from the oven.’

Now if anyone else had said that to me I would have groaned, maybe shaken my head. Out of politeness I smile a, ‘yes’.

We sit gazing at the Christmas nativity scene, backlit, as we eat our utterly delicious chicken pies and I, for one, believe in miracles. Yes, I feel fine.

*(I know, I said it was a Land Rover before, oops)

PS: Even now the thought of that pie makes me feel great, makes me smile, makes me happy. I wish I could eat one now.

Thank you, readers, whoever you are, wherever you are, for persevering with this saga, for helping me pull it out of my head. I’ll tackle something different soon. Meanwhile, I’m looking forward to a really good night’s sleep, at last.

No need for thanks, it’s been a great read. Since, with enormous pleasure, I read “the book” I’ve been following your blogs one or two at a time from the beginning. Last week you left Swaziland, back in October, so to stay in Africa I clicked on “Swamps, in Africa…”. I knew “Tex” had been to B…….u to collect samples from the B…a there for DNA analysis and had met with difficulties, but that’s all. So it was very interesting, and entertaining (thank goodness it was them and not me), to read about the actual expedition, described in such a graphic way and from a personal point of view. Thanks very much for that. I weekended at Samfya, crossing the Katanga pedicle and the Luapula from the Copperbelt, in 19.., and last year saw a TV documentary on the area, which helped to visualise your tribulations, though without the rain of course. But I’ve never seen a black lechwe, so lucky you anyway.

I’m sorry to hear the Zimbabwean farmers behaved so badly, especially as they have been welcomed in Zambia.

But what’s happened to Professor Lamb? Not a peep since February! I hope she’s not unwell. Busy with courses etc. I expect. Please express my admiration to her.

LikeLike

Even the words ‘Black Lechwe’ make me breathe in sharply! That fly. Eeurgh. It was a bad trip. But I have passed on your message to Lizzie and she has responded with a minor update on her FaceBook status, or so she tells me! Marking, she said…

LikeLike

Just couldn’t put the computer down! Such a good read…even makes turkey and tinsel seem like a reasonable option for once.

LikeLike

Thank you Judy! I’m glad you enjoyed it – that trip was one of my worst though the road trip was not what you might call fun either – Pioneer Camp is always such a haven after these unhappy experiences. After the swampy one when we got back – after the miracle of the Fringilla chicken pies – there was only the cottage free and we sat outside in the humid sunshine feeling like all was well with the world after all. Paul has done a great job on the place 🙂 Mx

LikeLike

As I read your accounts, I sometimes find myself holding my breath. I want to know what will happen next, and yet I’m a bit afraid to find out. However, I can’t stop reading. You set the words down in such a straightforward manner that I keep following them to their conclusion. You have a distinctive voice.

LikeLike

Hello Paula and thank you so much for saying this – it’s taken a while but I think I’m getting there with the voice thing. And if I may say so, your posts are really distinctive – I enjoy reading them and seeing things from your angle! As for the tales I tell – sometimes they have just been so frightening in real life that I find it hard to write them down – I’m not a naturally brave person I don’t think – but have been faced with situations I find scary and just had to lump it! Other people would find them tame I’m sure. But we are – cliche alert – all different!

LikeLike